The Second Renaissance: a very short introduction

This essay provides a short introduction to the 'second renaissance' as a framing for moment, movement and paradigm

This essay provides a short introduction to the “Second Renaissance” as a framing for:

The present historical period as a ‘time between worlds’ where our current civilization is in crisis and a new one is emerging

The new cultural paradigm or paradigms starting to come into existence

The growing ecosystem of people and organisations acting to steward and accelerate its emergence

The second renaissance is a response to the breakdown of modernity: to the crises modernity is driving and its inability to address them. Inherent to the Second Renaissance is the potential for the (re)birth of something radically different.

We argue that at the moment, the Second Renaissance is characterised by the following four premises1:

Real risk: There is a real risk of civilisational collapse and large-scale destruction of life due to intertwined ecological, political, social, and meaning crises.

Root cause: The root cause of these crises lie with the cultural paradigm of modernity: in entrenched individual and collective ways of being, which are conditioned by modernity’s logic and values.

Radical response: We are unable to address current crises through the logic and value systems that created and continue to drive them. We need responses that are radical in the etymological sense of going to the roots. That is, we need profound shifts in our ways of being, thinking, feeling, and acting: a new cultural paradigm.

Real possibility: A transformation of cultural paradigm is possible and is already starting to happen.

We would identify those who are closer to the “centre” of the Second Renaissance movement by their tendency to resonate with and be motivated by these core premises.

There may be multiple “centres” within the Second Renaissance movement: for example, different clusters of actors may agree largely with the above high-level premises but diverge on approach.

The Second Renaissance itself may also be one centre within a movement of movements – one part of the proverbial elephant. Making sense of a) the differences and divergences within the Second Renaissance movement and b) how the Second Renaissance relates to other concepts and movements is essential to the ecosystem mapping work we are doing.2

In short, the Second Renaissance is a name for this historical period based on an interpretation that we are in a “fertile void” in which it is becoming clearer that the major cultural paradigms of modernity and postmodernity are breaking down, and at the same time the possibility for newly forming paradigms is ripening.

This fertile void can be a state of lostness, confusion, disorientation, and despair – but crucially it might be the gestation period for something new to be born. It is a precarious time, in which the “new” waiting to be born is indistinct and unknown, and it is uncertain whether it will really arrive and flourish – but it is also a time of expectancy, hope, and possibility. It is a time for caring and tending to the gestating future, whose seeds are among and within us now.

Below, we go into further detail on each of the above premises, before outlining why we think such a framing matters and what a Second Renaissance emerging paradigm might look like.

NB: for more detail see our longer white papers at https://secondrenaissance.net/paper

Core Premises

1. Real risk: of civilisational collapse and large-scale destruction of life due to intertwined ecological, political, social and meaning crises

Life and civilisation as we know them are facing multiple existential and catastrophic risks. Signs of breakdown are evident in the multitude of global-scale crises we are facing, including:

ecological and climate crises, such as mass extinctions, biodiversity loss, and extreme weather events;

meaning crises, such as a mental health epidemic and a loss of meaning and purpose;

political crises, such as increasing polarisation, culture wars, identity politics, international armed conflicts, and the rise of authoritarianism and populist nationalism;

economic crises, such as rising inequality, declining quality of healthcare and education, and the fragility of various financial systems.

Many of these crises also interconnect with and exacerbate each other. As such, this constellation is increasingly referred to as a polycrisis or metacrisis.3

This is not just a “rough patch”; there is no certainty that “everything will be alright in the end”. Business-as-usual is neither sustainable nor desirable. The risks that we face are unprecedented in human history, due to the scale and reach of the technologies that we now possess, combined with the complexity and interconnectedness of our global civilisation. Never before have humans had such capacity to wipe out life on Earth.4 Moreover, the trajectory that we are currently on (particularly under “business as usual” scenarios) appears to be one of increasing existential and catastrophic risks.5

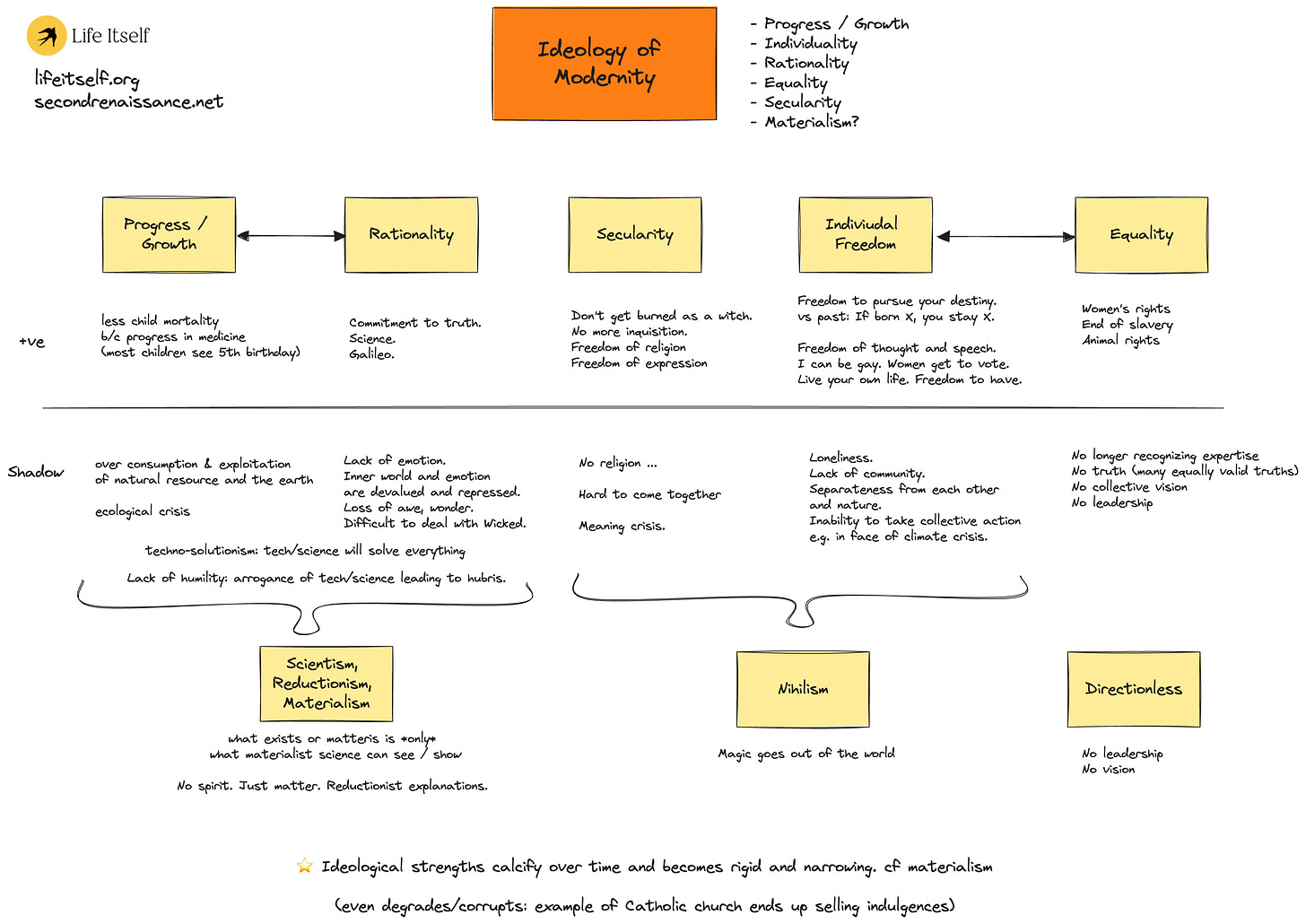

2. Root cause: The root cause of these crises lies in the cultural paradigm of Modernity: in entrenched individual and collective ways of being, which are conditioned by Modernity’s logic and values.

We see Modernity as a cultural paradigm, or worldview – that is to say, a way of making sense of reality and acting in the world. It is frame and filter: it both sets the limits and bounds of what we can or cannot see, and shapes our perceptions and interpretations of what we do see. Modernity is not objective or neutral: it has a logic and value systems which inform how we think, feel, act, communicate, design policies and institutions, and so on.

Modernity has been the dominant paradigm in Western societies for the last circa 400 years. Some of its fundamental views and values include: linear progress and growth, science and rationality, secularism, individual freedom, and equality.

There is much to celebrate and appreciate about Modernity’s developments. However, Modernity has “run amok” and what once were strengths have become liabilities: overvaluing individual freedom turns it into hyperindividualism, driving a loneliness epidemic and social polarisation; overvaluing rationality turns it into hyper rationalism, where emotions are unhealthily repressed and the wisdom of intuition, instinct, and other forms of knowledge are lost; and overvaluing economic growth is driving overconsumption and exploitation of natural resources and human labour.

3. Radical response: We are unable to address current crises through the logic and value systems that created and continue to drive them. Therefore, we need profound shifts in our ways of being, thinking, feeling, and acting: a new cultural paradigm.

We will be unable to truly address current crises – and cultivate radically wiser and weller futures – if we do not go to the roots. If a meadow is overrun by thistles, you can remove the heads and gain temporary relief – but they will grow back. To free the meadow of thistles, you need to go to the roots.

Similarly, it is the cultural roots of Modernity that are at the source of our predicament. And so we must transform that core of views and values by which we make sense of the world, evaluate our actions, and design the physical and social infrastructure of our societies.

The crucial argument here is that a) we need radically different systems, not incremental reform of existing systems and b) we cannot design radically different infrastructures and institutions without cultural transformation – the “primacy of being” thesis.6 Without different logic and value systems than those of Modernity, we will be unable to envision and implement radically different possibilities.

To get more concrete and more detailed about how delving more deeply into paradigmatic roots might inform responses to contemporary crises, we can look at two examples: global heating and runaway tech.

A technical analysis of the acceleration of global heating caused by growing carbon emissions might conclude that transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energies is a core solution. A deeper analysis might bring in systems thinking and interdisciplinary perspectives to look at systemic causes and solutions: for example, bringing in behavioural science and psychology to look at how advertising and media influence patterns of consumption and attitudes towards material waste.7 An even deeper level of analysis would delve into the cultural paradigm roots of systems such as advertising and media, to inquire into what continues to drive high-levels of consumption even while evidence of the dangers of climate crisis is increasing. This kind of analysis identifies a need to shift the cultural focus on endless material growth which is core to capitalism and all major modern societies – as well as to relinquish the dominance of “left-brain” linear and analytical thinking which give rise to delusions of control and make it difficult to grasp ecological dynamics and systemic complexity.

Similarly, the risk with AI development may seem superficially to be about increasing or improving regulation. However, fundamentally, it stems from a “left brain”-dominant, materialist obsession with technology, combined with a lack of patience and collective ability to coordinate collective action problems. The point is not that we do not need to transition to more green energy, or to regulate AI, but that that does not go nearly far enough and hence as “solutions” they are likely doomed to fail – like thistles whose roots remain, these problems will rapidly “come back”, whether in identical or similar forms.

4. Real possibility: A transformation of cultural paradigm is possible and is already starting to happen.

Inherent to the framing of the Second Renaissance is a belief that this kind of transformation is possible because, a) there are historical precedents for similar cultural paradigm shifts, and b) we see a growing number of individuals and groups actively practising different ways of living and working together in service of socio-ecological transformation.

There have been at least three major paradigm shifts since the Palaeolithic period.8 The first was from the animistic worldview of tribal societies, characterised by magical and ritualistic thinking, to the "Faustian" worldview of agricultural societies following the agricultural revolution, characterised by mythical thinking. The second major transformation occurred during the Axial Age, from the faustian paradigm to the "post-Faustian" (or "traditional"), consisting of the mythic-rational, transcendental thinking of religious society. The third such transformation started with the (first) Renaissance, intensifying with the Scientific Revolution, from the post-Faustian paradigm to Modernity, which is based on rational, scientific thinking. Our view is that we are currently witnessing the beginnings of another such transformation, from the Modern paradigm to something new. Later on in this essay, we outline some of the defining features that we consider to be characteristic of the emerging Second Renaissance paradigm.

Over the last few decades, we have been observing the emergence of a network of groups and individuals, whom we consider to be working towards a Second Renaissance. Thanks to the ease of communication and collaboration afforded by the internet and other digital technologies, this ecosystem has been growing in influence and scale in recent years, and multiple projects are working on developing coherence and coordination for collective action within it.9

Why does the Second Renaissance framing matter?

Why articulate the concept of a Second Renaissance? Why does it matter? Is it even a mistake to try to “define” something like this?

First, because this is a time of great risk and great possibility: a “fertile void” and decisive turning point in the evolution of humanity and life on earth. The collective narratives, beliefs, and worldviews by which we orient, navigate, and act in the world matter more than ever.

Secondly, a concrete framing and vision helps people to find others with aligned thinking and approaches.10 This, in turn, is crucial to more strategic and coordinated communication and collective action.

Thirdly, to further a conversation: it is easier to engage in constructive debate when there is something concrete to grapple with.

Ultimately, we see the Second Renaissance as a hopeful framing which supports collective action insofar as it involves meeting reality as it is – soberly confronting the real threats and risks to civilisation in the form of armed conflicts, environmental disasters, pandemics, threats to freedom and so on – and yet patiently and diligently acting to steward and accelerate the birth of a new cultural paradigm or paradigms.

This is also still a time of great uncertainty. The Second Renaissance faces multiple challenges. For example: firstly, complacency, blind optimism, or fear might lead people to underestimate, deny, or ignore the risk of civilisational collapse and large-scale destruction of life. Secondly, it is hard to see clearly and question your own most deeply-rooted values, beliefs, and assumptions, especially when they are shared collectively at the societal level: what is taken for granted as “normal” and “true” slips easily under the radar. Thirdly, many people, especially in the Global North, continue to benefit from Modernity while being largely protected from its harms – and people in this position may be less likely to engage with the premises set out above.

What does a Second Renaissance look like?

We have proposed as core to the Second Renaissance framing that a transformation of cultural paradigm is both necessary and possible – and that it is already underway.

There are many perspectives and approaches within the Second Renaissance movement regarding what the “new” cultural paradigm looks like and how to get there. In discussing a “new cultural paradigm”, we note some caveats:

There may well be a plurality of emerging paradigms as opposed to a single, global paradigm.

“New” does not necessarily mean entirely novel, but rather might refer to, for example, new syntheses or combinations of existing ideas and practices – or existing ideas and practices taking root in new contexts.

The writers of this essay are based in a European context. We wish not to make claims for the universality of our perspective, and welcome feedback where this might seem to be the case.

That said, we wish to offer an initial, rough sketch of some of the principles/values/dispositions that characterise the emerging Second Renaissance paradigm(s). This is based on what we see in networks we are part of or close to, what we speculate, and what we hope to see in the world.

The Second Renaissance emerging paradigm that we see is founded in a set of values/principles/dispositions including:

Inner Growth and Wisdom

Interbeing

Wholeness and Integration

Inner Growth and Wisdom

This refers to valuing inner growth and learning instead of material growth as a measure of individual and collective “success”.11 Inner growth and the cultivation of wisdom involve psychological, emotional, spiritual, and cognitive development, and the cultivation of qualities such as compassion, equanimity, humility, and discernment, in order to become good elders and ancestors. Individual and collective learning are valued as ongoing and non-linear processes: wisdom is not a pre-defined goal or static end result. Rather, inner growth and learning are part of collective evolution – developing abilities to respond dynamically, creatively, and appropriately to an ever-changing world.

Interbeing

Interbeing is a term coined by Zen Buddhist leader Thich Nhat Hanh.12 It refers to the deep interrelatedness and interdependence of all life. Valuing interbeing entails: recognising and taking seriously that we all live and grow within webs of interspecies interdependence; recognising and taking seriously that our wellbeing and our suffering are interwoven with the wellbeing and suffering of other beings; and allowing this recognition and knowledge to inform how we relate responsibly to each other, our communities, and the wider world.

Wholeness and Integration

This refers to a valuing of wholeness through the integration of polarities, especially in cases where one side of a polarity has been systematically suppressed, devalued, or neglected. For instance, valuing: intuitive and rational ways of knowing; artistic and scientific approaches; nonverbal and verbal communication; embodied and intellectual forms of intelligence; archetypically feminine and masculine qualities; sacredness, ritual, and ceremony, as well as secularity; community responsibility and accountability, as well as individual freedom and autonomy, and so on.

Conclusion

In this essay, we have outlined the concept of a Second Renaissance to describe the time we are living in; the potential of an emerging new paradigm(s); and a movement of people who are acting to bring this about. We have set out four core premises that we believe characterise the Second Renaissance and its movement, at the moment, and three characteristics of the emerging paradigm: inner growth and wisdom, interbeing, and wholeness and integration.

In writing this essay, we hope to invite conversation and grapple together with what it means to be living in this moment of great crisis and great possibility: in this turning point in history, in this “time between worlds”, at the beginning of a Second Renaissance.

Colophon

Original authored by Catherine Tran, Rufus Pollock, Elisa Paka, and Sylvie Barbier in March 2024 and published at https://secondrenaissance.net/intro

Echoing the ‘four noble truths’ are the core of the Buddhist dharma, we sometimes informally refer these as the `four noble beliefs’ of the second renaissance.

See Second Renaissance Mapping & Sensemaking: What we are working on at Life Itself Research, 7 Mar 2024, Life Itself

Strictly, we would suggest a polycrisis corresponds to the situation we have outlined in premise one — an escalating set of interconnected crises. A metacrisis is defined by premise one combined with premise two — that the root of the crises lies at the foundational ‘meta’ level of our civilization (the foundations being our ways of thinking and being shaped by the dominant socio-cultural paradigm of modernity).

Aside for the more sociologically minded: our presentation inverts the classic base and superstructure story of Marxism in which economic relations form the base and culture is the superstructure (derived from the economic base). By contrast here, culture and being are foundational, with institutions and technology building on that. Of course, the three layers interdepend with each one contributing to and shaping the others. In this sense, we think it useful to thing of the metaphor of the two hemispheres of the human brain and the work of Iain McGilchrist: we need both hemispheres and each contributes to the other, nevertheless one can have ‘primacy’ in shaping how we see the world. So whilst culture, technology and institutions all contribute to our civilization we see culture as having primacy, especially in driving paradigmatic shifts in our collective capacities. See https://lifeitself.org/primacy-of-being for more.

This idea is captured in the naming of the “Anthropocene” as a geological epoch in which humans have unprecedented and significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems.

Even mainstream actors such as the World Economic Forum are now flagging these concerns: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/09/beyond-business-as-usual-addressing-the-climate-change-crisis/

‘The Primacy of Being’, Life Itself, https://lifeitself.org/primacy-of-being

For example, see ‘Human ‘behavioural crisis’ at root of climate breakdown, say scientists’, 13 Jan 2024, Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/jan/13/human-behavioural-crisis-at-root-of-climate-breakdown-say-scientists.

See e.g. Jean Gebser, The ever-present origin: The Foundations and Manifestations of the Aperspectival World (Ohio University Press, 1984). Ken Wilber, A Theory Everything, (Shambhala, 2001) and Sex, Ecology and Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution (Shambhala, 1995). Hanzi Freinacht, The Listening Society: A Metamodern Guide to Politics Book One (Jægerspris: Metamoderna, 2017).

For a “map” of this emerging ecosystem of change agents, see https://ecosystem.lifeitself.org/ . For other similar ecosystem mapping efforts, see https://ecosystem.lifeitself.org/wiki/overview-mapping-efforts.

N.B. This could just as well be through helping people to clarify where they do not align with a particular vision or framing, as well as where they do.

Related concepts and frameworks include: Bildung, see ‘Better Bildung, Better Future: A Bildung Manifesto for a Global Renaissance 2.0’, 9 May 2021, Global Bildung Network, https://www.globalbildung.net/manifesto/; Growing up, cleaning up waking up, and showing up, from Ken Wilber, The Religion of Tomorrow: A Vision for the Future of the Great Traditions (Shambhala, 2017); and Cash Ahenakew, ‘Towards Eldering’, Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures Collective, https://decolonialfutures.net/portfolio/towards-eldering/.

For a short introduction to the concept, see Thich Nhat Hanh, ‘The Insight of Interbeing’, 8 Feb 2017, Garrison Institute, https://www.garrisoninstitute.org/insight-of-interbeing/, excerpted from Thich Nhat Hanh, The Art of Living (New York: Harper Collins, 2017)

“Emptiness does not mean nothingness. Saying that we are empty does not mean that we do not exist. No matter if something is full or empty, that thing clearly needs to be there in the first place. When we say a cup is empty, the cup must be there in order to be empty. When we say that we are empty, it means that we must be there in order to be empty of a permanent, separate self.

About thirty years ago I was looking for an English word to describe our deep interconnection with everything else. I liked the word “togetherness,” but I finally came up with the word “interbeing.” The verb “to be” can be misleading, because we cannot be by ourselves, alone. “To be” is always to “inter-be.” If we combine the prefix “inter” with the verb “to be,” we have a new verb, “inter-be.” To inter-be and the action of interbeing reflects reality more accurately. We inter-are with one another and with all life.”